AI for Design: It Starts with a Mindset

AI can help designers in lots of ways. This is the first piece in (what I hope is) a set of articles about the most promising use cases I have seen in the last year. If you have thoughts about these - or have experience with other exciting use cases - feel free to reach out to me on LinkedIn.

Parked beside Pier 86 in Manhattan is the USS Intrepid, an aircraft carrier put into service in 1943 that helped the U.S. win two of the 20th Century’s biggest wars. On top of it are some of the icons of aviation history - the Douglas A-4 Skyhawk, Lockheed A-12 Blackbird and, of course, the Grumman F-14 Tomcat (a favorite of anyone born before 1986 who likes movies about volleyball). Each is a supreme example of leveraging modern technology to push the boundaries of human capability.

Grumman F-14 Tomcat

Down below, off the side of the ship and on the pier all by itself is the Concorde, a relic from the late 20th century that offers a different story. Like the other jets there, the Concorde broke new frontiers when it went into service in 1976 as a supersonic commercial plane, capable of reaching Mach 2 and traveling from New York to London in just over 3 hours. But unlike the others, its decommissioning in 2003 is largely looked back at as the end of a failed commercial experiment. In spite of its speed, the Concorde had serious constraints that were incompatible with passenger air travel: it was fuel-inefficient and loud, and had limited range and low passenger capacity.

Supersonic jet engines are a marvel of modern ingenuity. They have practical use cases in which they are by far the best technology to fit the need. But the Concorde proved that commercial air travel isn’t one of them.

The Concorde, mounted on the pier below the space shuttle, in a measure of unintended symbolism (Image source: Wikimedia Commons).

Like the field of jet propulsion, artificial intelligence is driving change in the way we approach design (if not because of its impact to date, then certainly because of all the buzz about it). It offers opportunities to enhance existing business models or create wholly new ones. But to do so successfully, we need to be guided by both its strengths and limitations.

Like many designers, I have set out to broadly understand how AI is impacting architecture, engineering and construction. Recently, the number of apparent use cases has ballooned. To stay organized on the topic, I have sought to understand how and where each use case impacts the standard workflows designers use. In this article, I want to explain the way I visualize those workflows. In subsequent articles, I plan to share the specific use cases that align with each step in our workflows. But before we cover workflows, let’s focus in on some key strengths and limitations of AI in the context of Architecture, Engineering and Construction.

Strengths

Like other forms of automation, AI is something we employ to speed things up. In contrast with our other automated tools, AI can contend with large or complex problems without compromising on speed. This becomes important when our existing tools - spreadsheets, scripts and solvers - require long run times. And it is especially important when those run times limit the number of design options we want to study.

We can also use artificial intelligence to enhance our outputs. In contending with lots of data, AI can surface insights and exogenous impacts that a human may miss entirely. This is valuable when design decisions need to be made on the basis of a complex set of performance criteria, and distilling each option down to simple KPIs would be too reductive.

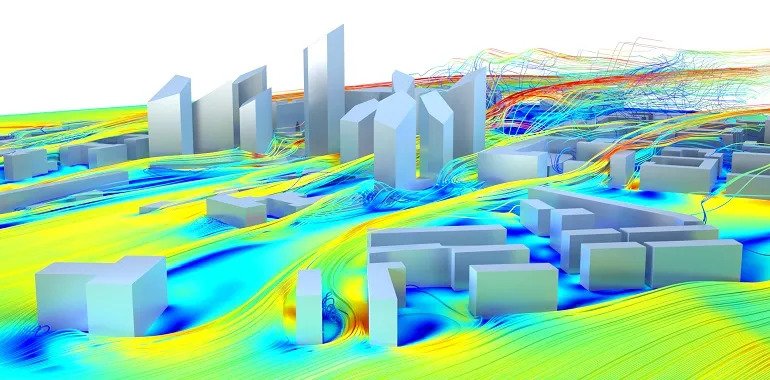

AI models (specifically Generative Adversarial Networks) have demonstrated an ability to predict wind interference effects of other tall buildings within an urban cluster, something that would be exceptionally difficult for individuals to do without extensive testing.

Another notable strength of AI is its ability to learn and adapt. In practice, learning and adaptation is achieved either by updating the input datasets on which the model is based (training) or adjusting the way the outputs are interpreted (inference). This enables us to automate steps in our workflow that were in the past precluded because of large, varying input datasets (think embodied carbon or permitting), or where our understanding of the right answer continues to evolve.

Limitations

Just like jet propulsion, AI has its limitations as well. It requires specialist expertise to implement in a manner that provides reliable outcomes. This means an organization must either build in-house capabilities or rely on third-party consulting or vendors.

It also requires a lot of data. For AI to be meaningful, input data needs to be robust and broadly reflective of the expected range of outputs. Preparing this data often takes a lot of effort, and if it is a dataset that will keep growing, it also requires good organizational governance over data collection.

AI can dramatically accelerate wind analysis. But for the results to be reliable, the model needs to be trained on enough data to fully capture the wide range of possible building shapes and surrounding environments. As a result, the AI models for wind analysis that I have found are built for fairly narrow use cases, and even then they still require massive amounts of data to properly train. (Image source: sweco.fi)

Many AI models require significant computational resources, especially for training. Often, this is done using third-party cloud services that are either set up by the designer or by the vendor providing the AI model. Designers seeking to build AI models locally (as they would with spreadsheets or other conventional pieces of automation) are at risk of running into scaling issues eventually.

As these limitations suggest, throwing AI at a problem is not a guaranteed home run. But the wide range of use cases shared by members of the AEC community demonstrate that there are many places within our workflows where the strengths of AI offer value and its limitations can be properly managed.

Mapping our Workflows

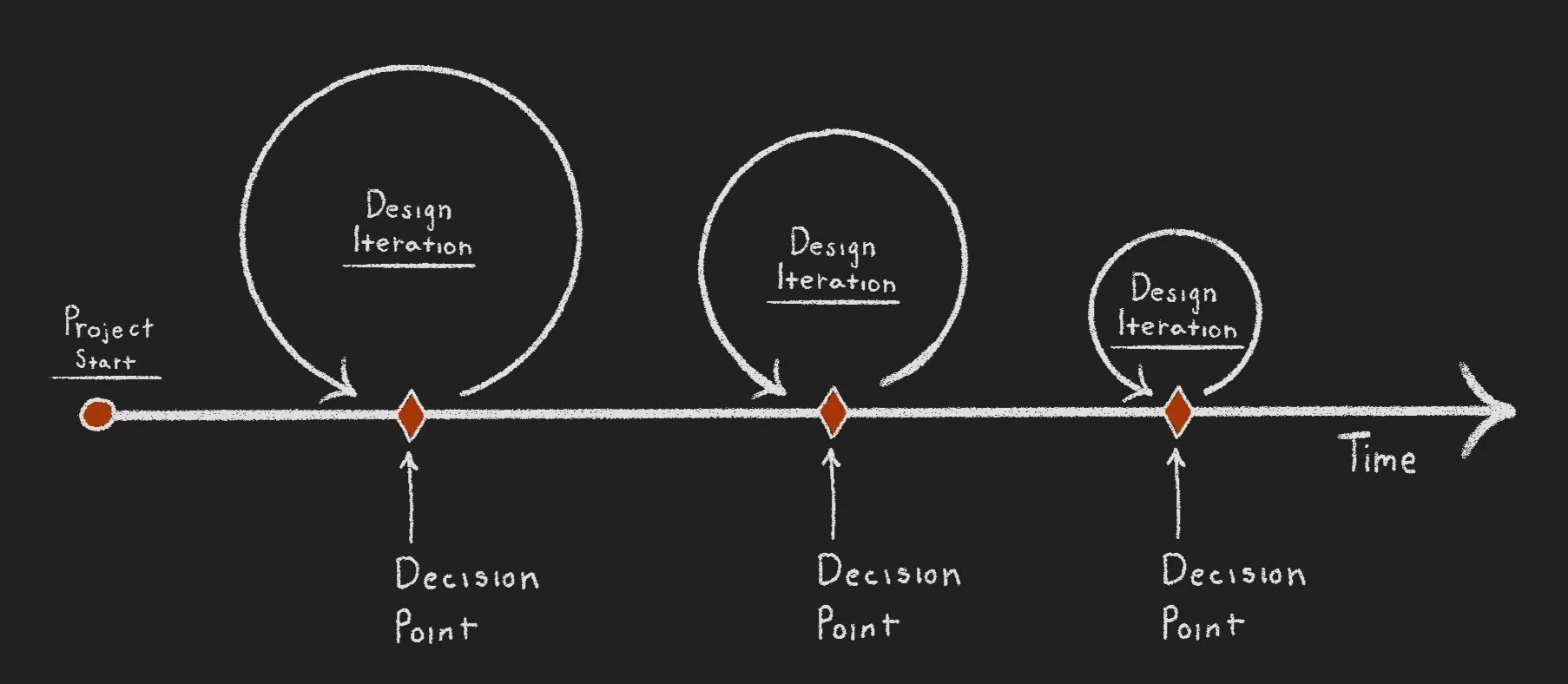

If you’re like me, you bristle when your project workflows are characterized as linear. For most of us, the project lifecycle consists of a series of design iterations, in which options are explored. Those options are judged against the project requirements at key decision points. If one or more options suffice, the project progresses to a subsequent phase (e.g. schematic design, construction documents) in which those options are studied in greater detail. Over time, big decisions (site layout, massing) are nailed down and the project team progresses to greater levels of detail as they ideally converge on a final design.

This is, of course, a highly idealized and generic project workflow, but it can help us understand the value proposition of new AI use cases. It’s also easy to sketch.

Simplified Iterative Design Workflow.

It takes a lot to get a project off the ground. At the project start, we define the design requirements in a way that helps us evaluate the design at key decision points. We also develop an understanding of the project context, including site context and pre-existing buildings and assets. There are many AI-powered services and solutions to help us start our projects off on a better footing.

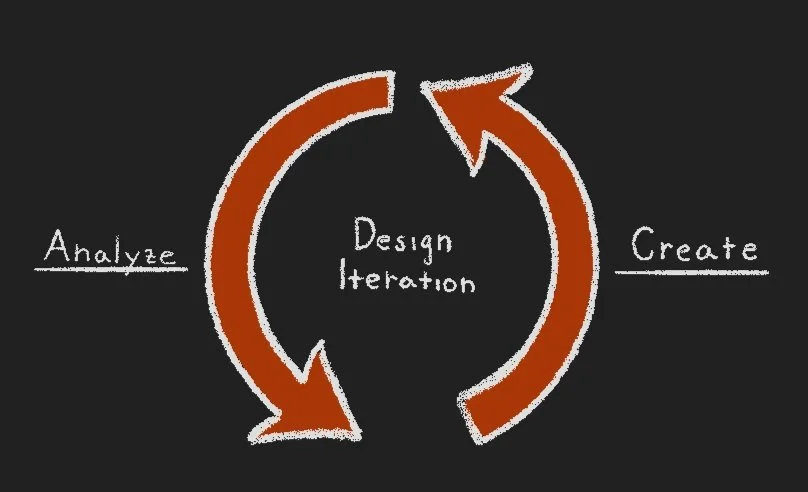

The two stages of a Design Iteration.

Our project then progresses through phases of iterative design. In each iteration, we create and then subsequently analyze our options. The results of our analysis then feed into decision points, when the project team evaluates the analysis outcomes against project requirements and determines whether the project can progress to the next phase or, alternatively, more options are needed.

It’s important think about the two stages of a design iteration individually. For decades, we have used technology to accelerate and streamline our work: spreadsheets for reusable and transferrable calculations, scripts to transform geometry, and queries to process data. These tools are great at helping us analyze our options. Our tools have not helped us nearly as much in our effort to streamline the creation of our options. It still takes time and manual effort to define and set up the design concept we seek to analyze.

To be sure, the way we create is different now than it was twenty years ago. Instead of producing a stack of sketches that give form to a design option, we spend days wiring up components in Grasshopper or Dynamo. But even with this digital tooling, our approach to defining and creating options is largely manual. And this persistent bottleneck is giving rise to some of the more exciting use cases for AI in architecture and engineering.

The design workflow is complemented by a project management workflow, which progresses alongside design and is of course key to the success of the project. The intensity of effort within the Project Management workflow varies across the project, and is generally the highest during the project start (to capture requirements, set up team coordination, etc.), at key decision points (to facilitate and document decisions and provide quality control), and at project closeout. Many of us have observed that Project Management is fertile territory for experimentation with AI, especially large language models. But getting good outcomes with AI in project management takes thoughtfulness and nuance.

The Project Management workflow progresses in parallel with design. The effort required for Project Management responds to key milestones in the design process.

AI Use Cases

These project workflows are simplistic, and every real project has plenty of instances where it veers from the typical playbook. But creating these generic workflows has helped me create a framework for organizing AI use cases. In the coming weeks, I’ll share more detail about the use cases I’m aware of, organized around the following activities:

Project Initiation

Creating Designs

Analyzing Designs

Project Management

We are in a time of exploration and experimentation, and there are no rigid guidelines for deploying AI across project workflows. As with all of our other design tools (which remain relevant and valuable), AI models - and the tools and services powered by them - have defined strengths and limitations. If we want to realize meaningful benefits in our adoption of technology we need to be sure the tool we pick fits the task at hand. We should be curious and playful with AI, but we should also be sure we are implementing enough of a structured approach to be able to measure outcomes. And we should keep an agile mindset - changing our design workflows is likely to be as iterative and nonlinear as the workflows are themselves.